Writings

in the general bibliography, writings by Vietri and about Vietri

Tullio Vietri, in “La Squilla”, Bologna, 18 December 1958

Tullio Vietri ( interview to ) November 1961

Tullio Vietri, in “Questioni d’arte”, July 1969

Tullio Vietri, About the pessimism of intelligence and optimism of willpower, in “Critica Radicale“, 1989

Tullio Vietri, in “Critica Radicale”, 1990

Having examined the theoretical positions and works of Giorgio de Chirico, and therefore highlighted the real meaning of his “realism of the enigma”, or his “enigmatism” as some define it; having examined the theoretical positions and works of Carlo Carrà (clearly distant from those of de Chirico), and therefore highlighted the real meaning of his “magical realism” or “mythical realism”, it remains to examine, not the theoretical positions (which appear never to have been expressed in written form), but the works of Giorgio Morandi. In order to highlight the real meaning of the “Morandi mystery”, as Francesco Arcangeli defines it (Giorgio Morandi, Einaudi Turin 1981, p. 87, already published by Edizioni del Milione in 1964). And therefore to answer the questions: is Morandi a metaphysical painter? Is he closer to Carrà or de Chirico? Evidently, after establishing whether his works follow the canons set by de Chirico for his metaphysical painting or by Carrà for his own. Undoubtedly, what Arcangeli writes (op. cit. pp. 86, 87) facilitates the examination: “Repressing that sentimental passion that did not fail to attract him”, Morandi took his metaphysics of 1918-19 … “to the height of authoritative and disinterested purity, that of the ancient Mediterranean tradition, of plastic so humanly deified, as to include in itself a motionless philosophy of moral hierarchy, of sacred discipline, of harmonious and unchangeable order”. And all this can be deduced from a careful reading that Arcangeli himself makes of the works of this period, in which “light is bewitched, an impossible noonday without escape besieges the objects, but everything is dominable, and dominated by the eye and the mind (…)”. I would say that one could agree with Arcangeli’s words if that verb used at the beginning of the speech did not distort, as I view it, the real meaning of the positions expressed by Morandi. To repress, in fact, means to take away force by using force. Thus, to take force away from sentimental passion. The repressing virtue and the virtue of overcoming passion should be attributed to the “disinterested purity” of his painting, which is “that of the ancient Mediterranean tradition”. In fact, I do not believe we can speak of repression-surpassing sentimental passion in Morandi, just as we cannot speak of repression-surpassing sentimental passion in Picasso … In fact, Picasso says that art is drama, the fruit of moral tension, of ideas and emotions, of the emotions of the painter “constantly awake before the lacerating, burning (…) events of the world”, and who “is totally modeled in their image”. Painting is not decoration, but “an instrument of offensive and defensive warfare against the enemy” (Picasso’s Writings, Scritti di Picasso, edited by Mario De Micheli, Feltrinelli, Milan 1973, pp. 47, 69). (…) The Morandi-Picasso parallel (and obviously de Chirico, whom Leymarie’s words clearly refer to) does not seem bold. Also because these authors have another extremely important element in common: the great lesson of Cézanne. For Morandi, Cézanne’s lesson is undoubtedly fundamental. Since 1911 the strong emotional and formal tension of his works constantly refers back to Cézanne. To all of Cézanne, and not only to his last period, the period favored by official critics. And therefore to Cézanne’s painting that,evaluated as a whole, cannot but be described as dramatic. Cézanne’s painting, in fact, is always an expression of that strong moral tension, that lyrical impetuosity, that violent emotion, that revolt against what exists, which are the characteristics of his personality, as John Rewald attests (La Storia dell’Impressionismo, Mondadori, Milan 1976, p. 174). And it is precisely these characteristics that allow Cézanne (because “they resemble him”, Baudelaire would say) to deeply love Tintoretto and Michelangelo, Ribera and Zurbaran (and I would say El Greco, as Lionello Venturi acknowledged in his famous 1936 study on Cézanne), and Daumier and Delacroix. And through their lecture, to arrive at the period of Impressionism with the lesson of Manet … Of Manet who loved … above all that Velazquez … who came from Ribera and Zurbaran (and from El Greco, therefore) and who was loved by Courbet and Delacroix, by Daumier and Corot, by Degas and Renoir, as attested by Leon Paul Fargue (Velazquez, Editions du Dimanche, Paris 1946, p. 3). It was precisely these authors (and their lessons) that allowed Cézanne to arrive, as is attested by his drawings and his painting up to 1871/72, to a kind of expressionism that makes us think, at certain moments, of Nolde (see for example Autopsy, The Funeral Vanity set… ); and then between 1872 and 1878, to an Impressionism that became increasingly sui generis; indeed a sort of “post-impressionism”, characterized more and more by the rationalization-geometricalisation into “cylinders, spheres, cones, everything put into perspective”, as Cézanne himself says in a letter to Émile Bernard (reproduced in Cézanne, Lettere edited by Duilio Morosini, Bompiani, Milan 1945, p. 107). “Post-impressionism” is certainly not a sudden, voluntaristic, cold, constructivist rationalization-geometry of the natural object in its objective truth. Because it is not a simple “outgrowing” way out, of overcoming, of winning, what Lionello Venturi (La Via dell’Impressionismo, Einaudi, Turin, 1970, p. 263) calls “expressionistic – romantic forcings”… “Post-impressionism”, will characterize all his subsequent production, is instead a living synthesis, a composition of the various components that are therefore always present: the romanticism of revolt and simultaneously the classicism of the willingness to know and of everything dominated and dominable rationally. Of all that man must rationally dominate. To Cézanne “the Cubists owe almost everything. Picasso owes him a great deal,” says Duilio Morosini in the preface to the book cited above (p. 13) … To Cézanne, Morandi also undoubtedly owes a great deal. To his formal lesson because it is moral, and moral also because it is formal, he will always be faithful. Not only in the years 1911-1914, but also in the so-called Futurist phase (which is not Futurist, if anything Cubist) of 1914-1915. And in the following phase (1916-early 1917) characterized by the recovery of a certain lesson from the Viennese “secession” (Klimt), filtered most probably by the lesson he received from Augusto Majani, his teacher at the Accademia in Bologna, rightly remembered as a graphic designer, poster designer and talented caricaturist (he signed his name as Nasica in such works), one of the most typical and valid representatives of the “Bolognese school”, “faithful to a stylistic and ideological line that, in cases such as his, qualifies the Liberty style as a movement of democratic thrust and anti-academic approach” (Rossana Bossaglia, Il Liberty, Sansoni, Florence 1974, p. 124, 125). And probably from a certain lesson, obviously still Liberty (as seems to be attested by Fiori, dated 1917, in a private collection in Milan, at no. 31 of the Catalogo generale Vol. Primo 1913-1947, Milan 1977 by Lamberto Vitali) received by Bistolfi who in 1907 had been called upon by the Municipality of Bologna to erect the famous monument to Carducci the day after the poet’s death. (…) And to the same Cézannean lesson Morandi would also be faithful, obviously, in his so-called metaphysical phase (1918-1919) by painting the drama of extreme rationalization-geometrization. In analogy, if you like, with what Mondrian did, expressionist in the style of Van Gogh and then Munch in the years up to 1910-1911 (i.e. he was then around forty years old, after twenty years of painting, as Umbro Apollonio attests in Mondrian, Milan 1965, p. 4) and then cubist. (…) Therefore, that of Morandi is a rationalization – geometrization of a moral protest, of a resentment, of an indignation and at the same time of a hope in bourgeois common sense, in the ideals of the bourgeois tradition, in the freedom guaranteed by them, because “the supreme ethical concept is that of freedom”, as Umberto Scarpelli says (L’Etica senza Verità, il Mulino, Bologna 1982). Evidently without witchcraft or magic evocation, as Cesare Brandi rightly says, recalled by Arcangeli (op. cit. p. 79). Therefore Morandi in his ethical commitment is very close to de Chirico, and certainly not to Carrà, as it can be seen from his works. He is close to what de Chirico proclaims as calm, serenity and power as sense and reason for being part of art in its moralizing action (Zeusi l’Esploratore, of 1911-15, reported in Paolo Fossati, Valori Plastici 1918-22, Einaudi, Turin 1981, p. 87), with the exclusion of all anguish, given the certainty of perspective. Because “the power of the specialized intellectual, artist and genius, (…) must pose itself as a service of political struggle”, he says of de Chirico, “to change the factual conditions of the situation” (ibid.). De Chirico himself, later on, in Valori Plastici (Plastics Values) of 1920, still nourishing hope in his own action of moralisation (through his writings and works of art), in condemning the exaltation of war and the “futurist revelry” of D’Annunzio’s “futurism”, writes: “Hysteria and shabby behaviors are condemned at the ballot boxes. I believe that by now everyone is satiated with those behaviors, whether political, literary or pictorial” (quoted in Massimo Carrà, Metafisica, Mazzotta, Milan 1974, pp. 189, 190). Facing the serious political events of those years (1919-1922), organized violence, Fascism, this rational structure seems to mist over, it seems to crack both in Morandi’s art as in de Chirico’s. The perspective of effective action in the reality of their moral = social commitment falls. But they are both aware of the truth enunciated by Alberto Savinio in n. 5 of 1920’s Valori Plastici (reported in M. Carrà, op. cit. p. 243): “When in the mind of man the memory of yesterday and the hope of tomorrow are obscured, he faces the threshold of nothingness, of despair”. And to such despair they oppose themselves, in an extreme recourse to reason, with different outcomes, necessarily. In de Chirico, the relationship between past (Greece, Renaissance) – present (industrial world) – enigmatic future (“Homeric dawns”) falls, to give rise to a present without past or future (his painting until 1927-28), interspersed with the “Classical Romanticism” of the Roman Villas, narrated in its dramatic nature of cogent conditioning of the individual without individual space, without defense; and later, placing himself completely outside metaphysics as he had previously theorized, in the years 1915-1920, when he feels that this conditioning (the “law for the defense of the State” in November 1926, the dissolution of the parties, the end of the liberal state) cannot but affect his own person. He will transform in the ironic past of the fable, of the mockery, in the vainglory of individual abilities, of rare qualities of painter and intellectual that inevitably recall that secentism and that technicalism previously despised, because, he said, “in art, if it is true art, technique has no role” (Zeusi the Explorer, op. cit. p. 86); because “monstrous emptiness” and “fabulous deafness” “stand out and reign in the painting of that century (…)” (La Mania del Seicento in P. Fossati, op. cit, p. 251). In Morandi, on the other hand, there will be a search for salvation in the recourse to a certain naturalistic descriptiveness (1920-24) in the recourse to a certain impressionism (Renoir, above all), and thus in the arrival at a certain intimism. But it is a brief reconsideration of that lesson, of that conception of the world, to arrive at a certain hermeticism in the style of Montale, and not the “naive” hermeticism of Ungaretti-Carrà characterized by the “poetics of the absence of time”, as Giuliano Manacorda says (Montale, La Nuova Italia, Florence 1973, p. 19). A synthesis of all his previous experiences, favored by renewed loves for Giotto, Masaccio and Piero. All placed in a certain relationship with Cézanne, and the “tactile values”, as well indicated by Bernhard Berenson in his famous four books dedicated to Italian painting between 1894 and 1897. (…) This synthesis, carried out by Morandi in the years following 1924-25, is the formal synthesis due to the conquered faith necessary to live and survive, that will be “faith in poetry, meanwhile”, “whose object may be obscure and that consists”, as Montale says (Uomini e Idee edited by Sandro Briosi, quoted in Giuliano Manacorda, op. cit. p. 9) “above all in living with dignity in front of oneself, in the hope that life has a meaning, that rationally escapes us, but which is worth experiencing, worth living”. This lively and profound feeling is that same sentiment that from the contingent historical reasons allowed to men who would have liked to oppose them, but could not or did not know how to find, for ancient historical reasons, typical of that pacifistic and quietistic and democratic, even if not socialist, sector of the Italian (but not only Italian) petty bourgeoisie to which Morandi belongs, the necessary forces, the necessary connections for action. This lively and profound feeling is the same feeling that, for contingent historical reasons, gave men who would have liked to oppose it but, for ancient historical reasons, could not or did not know how to find the necessary forces, the necessary connections for action, typical of that pacifist and quietist and democratic, if not socialist, sector of the Italian (but not only Italian) petty bourgeoisie to which Morandi belonged. Morandi’s approach is therefore connected to a painting that is still dramatic, albeit in a reduced tone, compared to the previous one, in which the echo (not the immediacy) of the happiness of discovery of the sensibility that was of the Impressionists and many Post-Impressionists, resonates in him within the measure of a modest life, paid for by what exists, in an apparent reduction to the mere relationship between the subjective self – objective nature. It is precisely this apparent reduction that allows Arcangeli to bring Morandi closer to Wols and Fautrier, and thus to Morlotti and Burri. To the informal (op. cit., passim, in particular p. 133). And to sustain (op. cit., pp. 128, 129) that Morandi “has opened, with a very few others who are not only painters, the battered, exhausting, anguished path of certain slow, hidden Europeans: Wols, subtle and profound German, Klee’s heir, but tempered on the old misted, corroded glasses of the Paris bistros; Fautrier, sensualist, sometimes aggressive, more often exhausted”. And he adds “it is not that I dream of ascendancies that Morandi might or might not like, for the sake of topicality (…) He will say that I am extremely moved by the pathetic history of this painting, which began with the highest formal magisterium, and passed, degree by degree”, having sensed “the life of ancient residencies, the desperate sprouting of a few flowers”, to “this sober, sad, homely informel” (ibidem, p. 129) … But as is well known, Morandi did not accept, approve or admit these ascendancies and descendancies attributed to him by Arcangeli, given their evident moral and intellectual emptiness, their mere naturalism, because the formalism in him … the giving of rational form, necessarily rational, to his deep-seated emotions, dependent on his ethical conception of individual and social life in accordance with the principles of ethicality and responsibility, is an essential constitutive element, a permanent structural element, always present and traceable even in the most “crepuscular” moment. Arcangeli’s exaltation of the informal could not, therefore, not be interpreted as condemnation (and not exaltation as Arcangeli would have wished) of the formal-ideological components (always inseparable) typical of Morandi’s painting. And this is how Morandi interpreted it (as can be seen from a clear allusion contained in a letter Arcangeli sent to me on date April 22 1962? Had his essay already been submitted to Morandi on that date ? And from verbal testimonies of that time subsequently collected). Also because this interpretation found comfort in another fundamental misunderstanding of Morandi’s painting, even in the presence of an exact textual reading. Arcangeli in fact says, referring to certain works of 1929, that “From the exquisite and profound and at times almost Canova-like description of external appearances”, “Morandi tacitly goes down within himself”; and “without ever losing the reality of figuration he presses from within, with such desolate force that he almost creates, in the effect,” (thus, apparently) “a sort of reversal of the creative process that is proper to him. It really does seem, in a group of works (…), that Morandi started from an inner motif” (op. cit. p. 168). (…) That Morandi, Morandi’s painting, is an expression of the petty bourgeoisie is attested by Francesco Arcangeli (op. cit. p. 35). I would say, however, that it is an expression of that traditional quietist-pacifist and democratic, though not socialist, sector of the petty bourgeoisie, which differs in these characteristics from another sector of the petty bourgeoisie formed in the 19th century, at that time of economic and functional-structural decline. The represented sector, in its rebellious-eversive phase, by the intellectuals of the “1896 generation”, was that of the generation that suffered the defeat at Adua and experienced the “general disillusionment” that followed. Unitedly with the anguish generated by the organization of the working class and its appearance in the national political limelight, in those years, were the decisive events that gave rise to the new nationalist, anti-socialist and anarchist movement of D’Annunzio and Marinetti, of Mussolini and De Ambris, albeit divided into anti-industrialists and industrialists, at least until the Second World War (cf. Adrian Lyttelton, La conquista del potere, il Fascismo dal 1919 al 1929, Laterza, Bari 1974, passim, in particular pp. 27, 79). (…) The lesson of de Chirico and Morandi, therefore, cannot be forgotten. Just as Sironi’s lesson cannot be forgotten, it is not too distant from de Chirico and Morandi themselves, even if it must be appropriately purged. Sironi, metaphysician, firstly, a futurist sui generis like Morandi, and then a novecentista sui generis. Because it must be recognised that Sironi is one of the greatest artists of our century and that everything he did “was dictated by absolute good faith”, as Ettore Camesasca says (preface to Mario Sironi, Scritti Editi e Inediti, Feltrinelli, Milan 1980, p. VII). He was dictated by “artistic and human responsibility”, by a profound faith and a profound ethical conception that produced (notwithstanding the partiality and therefore the falsity on a scientific level, consequently objectively, of the problematic proper to the professed political theory, or rather I would say because of such partiality felt, experienced as a necessary irremediable contradiction with the ethical demands that as such pertain to man in general, to man as a species) a strongly dramatic art, with a tendency towards tragedy. Therefore an art that “in spite of everything, shows itself to be deeply involved with its time, for better or for worse”, as Ettore Camesasca rightly says (ibid., p. XII), noting that necessarily “making history” (and this is true for the historian, but also and above all for the artist, according to what Thomas Mann says in Lettere a Paul Amann, Milan 1967, pp. 59, 190) “means first and foremost recognising the society and ideas in which an event took place” and the way in which each artist handles faith in dominant social dogmas. Because it must be recognised that Sironi is in an obvious way, a sincere expression of that sector of the Italian petty bourgeoisie (and not) and its drama. That is, of that sector to which D’Annunzio and Marinetti belonged, and then Carrà and Soffici, Martini and Gentilini and Rosai, that sector of the petty bourgeoisie that believed it could oppose with violence and anti-industrialism the structural-functional crisis that was affecting the bourgeois individual. Their lesson, therefore, and the lesson of the historical avant-gardes that inspired them and the lesson of the movements that preceded these avant-gardes, as well as the lesson of the great masters from 1200 to 1800 that they loved, cannot legitimately be forgotten. Obviously by the artist-intellectual, “by the true artist” who necessarily “works without worrying about criticism and critics” as Cézanne says (Lettere, op. cit. p. 115). And who, therefore, opposes the craftsman-artisan, a mere manipulator at the beck and call of the ideologue-duce of Sarfattian memory, and consequently of the market. They cannot be forgotten by the artist-poet for whom necessarily art-poetry is an indissolubly coinciding intellectual and moral life, as Eugenio Montale teaches us (op. cit. p. 24).

Aligi Sassu, 1960

Gianni Celati, 1960

Stefano Bottari, 1962

Fortunato Bellonzi, 1968

Roberto Costella 2001

Gian Mario Villalta 2010

Roberto Costella, 2018

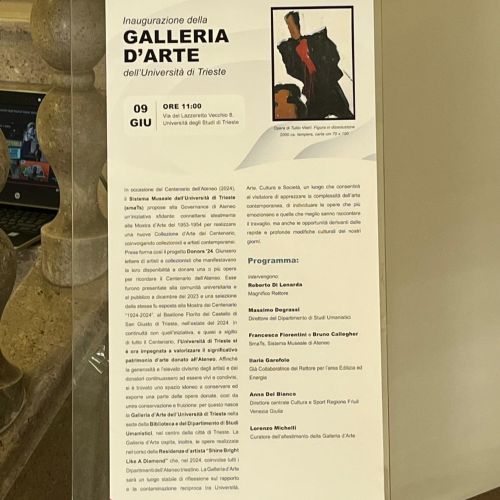

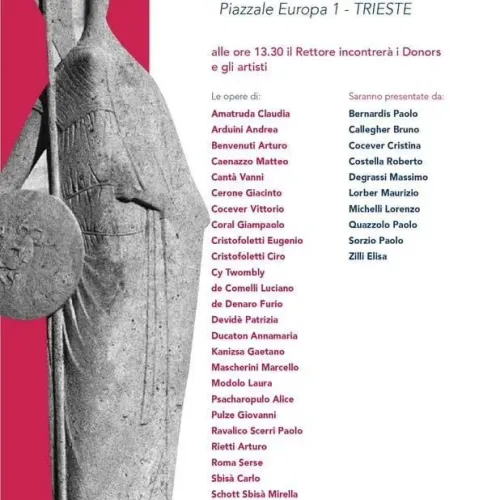

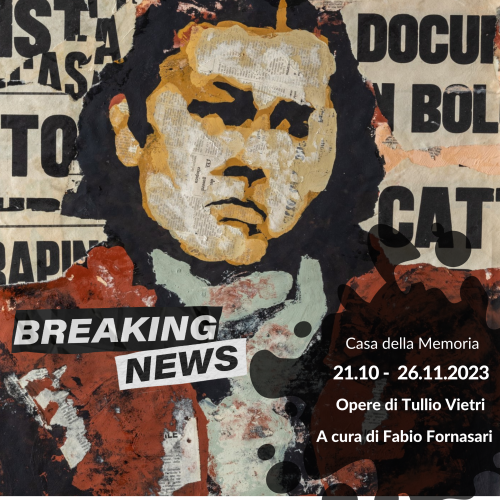

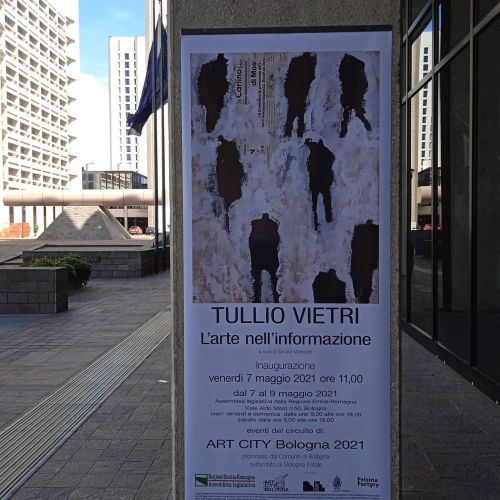

Events & News

Highlights of special moments, near and far.

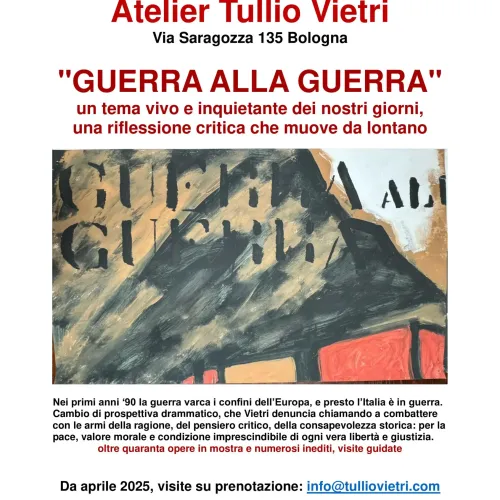

The Atelier

The atelier preserves the family’s rich pictorial and graphic collection (approximately 1,500 pieces, between paintings and graphics). It periodically organizes temporary exhibitions within its spaces, in order to promote knowledge about the collection, displaying the works in rotation.

It is located in Bologna in Via Saragozza 135 under the historic portico of San Luca.

The Atelier can be visited, by appointment, from October to June. Guided tours available.

The Museum

The Biblioteca Civica, managed by the Oderzo Cultura Foundation, displays the core of the collection owned by the Municipality of Oderzo, by the artist’s behest, custodian of his artworks (about 4000 pieces including paintings and graphics).

It is located in Oderzo (TV) in Via Garibaldi 80 at the Civic Library.

It can be visited during library opening hours and by appointment.